Shifting sands: Reform in Australian privacy and cyber security regulation

by Adrian Chotar, James Patto and Annie Zhang

In Brief

- With digital connectivity being ever more prevalent, data breaches will become commonplace, and Australia, as a wealthy nation, is an attractive target.

- Due to the piecemeal way it has developed, Australia’s current regulatory frameworks for privacy and cyber security can be confusing, sectoral and out of step with international equivalents.

- There is no panacea in legislating against cybercrime - all stakeholders - government and industry alike - must continue to work together to develop robust and streamlined regulations.

- This article outlines the current state of play for key proposals, reforms and review processes taking place in relation to Australian privacy and cyber security laws and regulations.

Cyber attacks are on the rise

Although it is only the start of the storm, 2022 will be remembered as the year the devastating impacts of cybercrime really hit home for Australians.

With state actors and cybercriminals using data to commit extortion, espionage, and fraud in Australia - with no sign of abating - it is inevitable significant changes are afoot for both the public and private sectors. What we have seen to date is just the tip of the iceberg for what the future holds for the Australian private and public sector alike. In the last financial year, the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) received more than 76,000 cybercrime reports (one report every 7 minutes), which reflects an increase of nearly 13 per cent from the previous year.

Ransomware remains the most damaging tool used by threat actors when combined with the exfiltration and publication of personal and sensitive data. In fact, according to the ACSC, every sector of the Australian economy was impacted by ransomware this year. And as the Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) business model continues to gather pace, all a threat actor needs is a way inside to deploy increasingly obtainable ransomware code into the target's systems. Further, with an average increase in cybercrime reporting costs up 14%, criminals have clearly clued into the prosperity of the Australian economy and the vulnerability of personal, business and government digital assets.

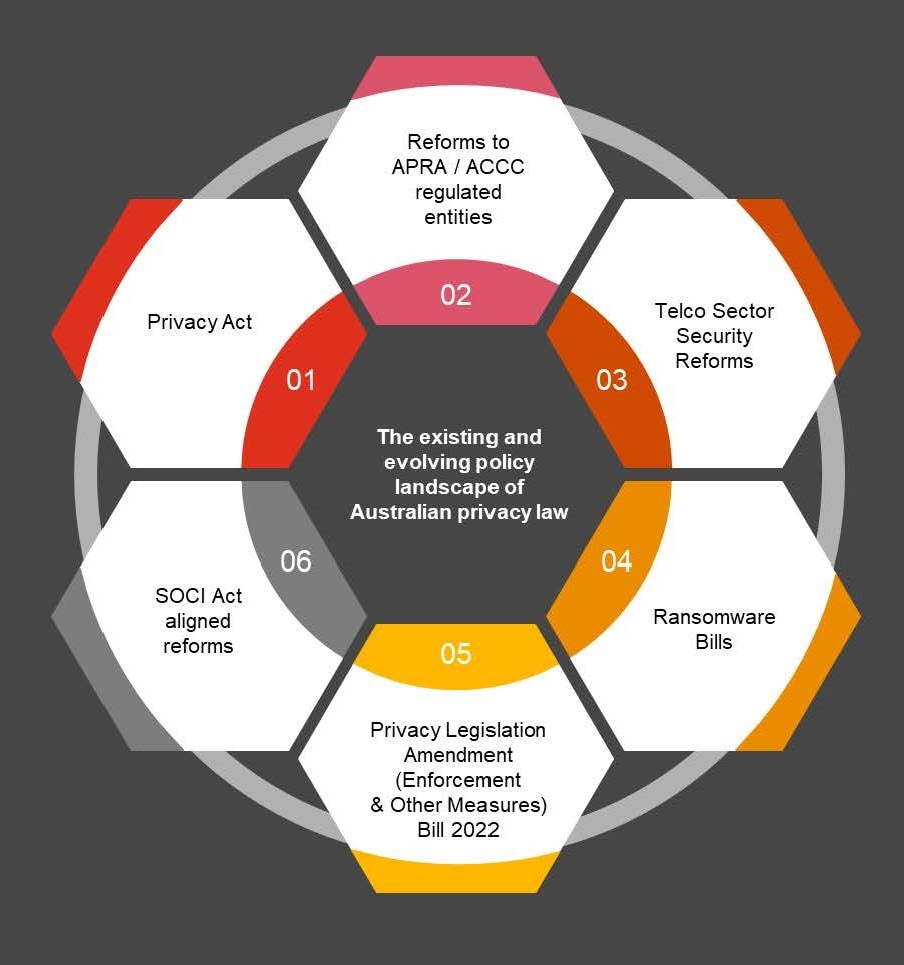

A spate of recent high-profile cyber attacks on prominent Australian-based businesses has pushed the dial to overdrive, kicking the Federal Government’s overhaul of the Australian privacy law into high gear. There have been several parallel proposals, reforms and review processes taking place in relation to privacy, data protection and cyber security regulation across the economy. With complex technology comes complex regulation and navigating the changing landscape is essential for business to remain secure not only in the present but to plan for the future. Set out below is a summary of the current state of play for cyber security laws and regulations in Australia.

The Privacy and Cyber Security Regulatory Landscape is evolving

1. Privacy Act Review

The Attorney-General’s Department is in the process of undertaking a comprehensive review of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) with recommendations expected to be released prior to the end of 2022 and the resulting reforms likely to be implemented in 2023. In October 2021, following feedback and early consultation, a Discussion Paper was prepared to elicit further feedback on the proposals to reform the Privacy Act.

The reforms canvassed in the Discussion Paper are wide-ranging and significant, and signal a desire to strengthen the Privacy Act to align more closely with a GDPR-style regime.

Image: Key themes extrapolated by PwC from the Privacy Act Review Discussion Paper (October 2021)

Key highlights included:

- changes broaden the scope of the definition of “personal information”;

- stricter requirements to “anonymise” rather than merely “de-identify” personal information;

- change to the current exemptions to certain requirements of the Privacy Act (such as removing or modifying the ‘employee records’ exemption);

- increased obligations around transparency and consent, including a requirement to add in express data purpose statements in privacy policies;

- new requirements to ensure that the collection, use and disclosure of personal information is undertaken in a “fair and reasonable” manner taking into account individual expectations, the sensitivity of the information concerned, foreseeable risks that may arise, and other legislated factors;

- new rights for individuals to object to the collection, use or disclosure of their information and to request the erasure of that information in certain circumstances; and

- an unqualified right for individuals to object to any collection, use or disclosure of personal information for direct marketing purposes.

In mid-January when speaking about the Privacy Act reforms, the Attorney-General described changes being considered as a range of 'modernisations'- which seemingly is signalling a move towards the European GDPR style model - with increased rights for individuals a centerpiece. Two key areas mentioned by the Attorney-General were:

- Right to be forgotten

This right has existed under the GDPR for some time and allows individuals to require an organisation to destroy all personal information that they hold on that person where it is no longer required for the primary purpose of collection or, in some circumstances, where consent of the individual is withdrawn. - Statutory tort for breach of privacy

This will grant individuals a right to take direct action against an organisation where a privacy breach has occurred. This could potentially apply to any obligation of an organisation under the Privacy Act including misuse of information, a failure to secure it properly or a failure to comply with data breach notification obligations.

In this context it is important to note that the Privacy Act does not treat a data breach as a breach of privacy in itself and as a result does not require a guarantee that information be kept secure. APP 11 requires organisations to take 'reasonable measures' to protect the personal information because it is basically impossible to guarantee security of information in the digital world without disconnecting everything from the internet.

It is evident from the Discussion Paper that the Australian Government is attempting to address the holes in the legislation as a result of burgeoning changes in the digital age. However, the Government cannot combat cyber threat actors alone – industry participants from corporate Australia must provide their firsthand experience to dealing with these criminals to help inform the development of legislation so that it remains realistic and achievable.

The Attorney-General is clearly looking at individuals rights as a key component of the Privacy Act Reforms.

In terms of the right to forget, whilst this seems simple, organisations will need to build relevant functionality into their systems and processes to receive and action these requests to delete the relevant personal information across all of their systems. In large diversified organisations with group-wide data sharing arrangements this can be a difficult task.

Similarly, guaranteeing deletion of information in complex IT environments where there are regular and diverse archives and backups is not straightforward. There is a risk that an organisation will not have actually 'forgotten' an individual if backups or archives still contain the personal information. This creates a conundrum where organisations are faced with the difficult decision of choosing between constantly amending archives and backups to remove data on request, or consider not backing up personal information holdings. This obviously in itself creates risk where organisations have obligations to protect personal information against loss of that information.

In terms of a right for individuals to take action for breach of privacy, organisations need to ask themselves, when (not if) they happen to be the victim of a cyber attack - are they taking 'reasonable measures' to protect personal information holdings? What are 'reasonable measures' in their circumstances? Is the organisation across how personal information is collected and stored in your organisation? Many organisations make the mistake of thinking that because they are across cyber security they are across privacy. Whilst cyber security is an important part of the privacy equation, privacy and data management goes well beyond cyber security.

With enhanced fines and these changes (and likely more on the way), organisations should seriously consider analysing their personal information management all the way from collection to destruction.

2. Reforms impacting on APRA and ACCC-regulated entities

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has its own set of Prudential Standards for the governance and management of cyber security risk, including:

- CPS 234: this standard requires entities to maintain a secure information security capability commensurate with anticipated information security vulnerabilities and threats.

- CPS 220: this standard sets out APRA’s requirement for regulated entities to have comprehensive risk management practices.

- CPS 230: APRA has proposed a new prudential standard, which will extend the scope of existing outsourcing (e.g. IT and digital infrastructure material providers) and business continuity requirements.

Commencing on 12 October, the Telecommunications Amendment (Disclosure of Information for the Purpose of Cyber Security) Regulations 2022 (the Amendment) introduces further measures to protect consumers who are victims of a significant data breach, including giving the right for telco companies, under certain circumstances, to temporarily share sensitive data (e.g. government-related identifiers like driver’s licences, passport numbers) with financial institutions for up to 12 months following a data breach. This will allow financial institutions to implement enhanced monitoring and safeguarding of customers whose accounts may be susceptible to fraud, scam activity or identity theft.

The financial institutions wishing to receive this data must be APRA-regulated and must also satisfy robust information security requirements. The financial institutions must also make undertakings to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) to honour their obligations under the Privacy Act, and that the information being sought must be necessary and proportionate, and will be destroyed when no longer required.

As showcased through the numerous sector-specific legislative requirements on cybersecurity, there is significant complexity in the Australian regulatory regime. The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) demonstrates this in its Cyber Security Governance Principles, where it states that “depending on the industry these [regulatory requirements and standards] can be overlapping.” Organisations need to keep abreast of the notification requirements to each of relevant regulatory and reporting body, e.g. OAIC, APRA and ACSC (and Home Affairs) in the event of a cyber incident. Failure to report may result in significant penalties.

3. Telecommunications Sector Security Reforms (TSSR)

The TSSR amended the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth) in the following manner:

- Security obligation: All carriers, CSPs are required to “do their best” to protect networks and facilities from unauthorised access and interference.

- Notification obligation: Carriers and nominated CSPs are required to notify government of planned changes to their systems and services that could compromise their capacity to comply with the security obligation.

- Information gathering power: The Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs has the power to obtain information and documents to monitor and investigate their compliance with the security obligation.

- Directions power: The Home Affairs Minister has a new directions power, to direct a carrier, CSP to do, or not do, a specified thing that is reasonably necessary to protect networks and facilities from national security risks.

The Telecommunications (Carrier Licence Conditions—Security Information) Declaration 2022 was registered on 5 July 2022, and requires carriers and eligible CSPs to:

- notify the Australian Signals Directorate of cyber security incidents impacting applicable assets; and

- report operational, control and interest information for each applicable asset to the Secretary of Home Affairs.

These requirements overlap with similar obligations contained in the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (Cth) (SOCI Act).

Organisations need to be hyper aware of sector-specific cyber security obligations that coexist alongside the Privacy Act. Unfortunately, Australia’s patchwork of privacy laws means that cyber security requirements may overlap and create confusion. Alignment should be a key goal to ensure organisations can bolster cyber security compliance without confusion. Duplication of regulation results in organisations expending funds to effect “compliance for compliance’s sake”, rather than spending that money on effective protection measures.

The Australian government is, once again, playing catch up to the European Parliament, which recently approved the directive on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union (“NIS2 Directive”). The NIS2 Directive provides legal clarity and ensures coherence between the directive and sector-specific legislation.

4. Crimes Legislation Amendment (Ransomware Action Plan) Bill 2022 (Coalition Bill)

The Coalition Bill was reintroduced to federal Parliament by the Shadow Minister for Home Affairs, Karen Andrews, as a private member's bill following its lapsing in April 2022 as a result of the dissolution of parliament due to the federal election. The Bill is intended to target perpetrators of ransomware attacks.

It would introduce:

- new criminal offences for cyber attackers (such as a standalone offence for any form of cyber extortion using ransomware);

- new powers for enforcement authorities (such as allowing them to freeze or seize cryptocurrency assets); and

- new maximum penalties ranging from 5 to 25 years imprisonment for those convicted of cyber crimes.

5. Ransomware Payments Bill 2021 (No. 2) (Labor Bill)

The Labor Government could look to enact the Labor Bill which was introduced by then-Shadow Assistant Minister for Cyber Security, Tim Watts, as a private member’s bill in 2021 when in opposition.

Importantly, the Labor Bill proposed:

- mandatory reporting requirement for entities (other than small businesses with an annual turnover of less than $10 million) that suffer ransom attacks;

- obligation for companies to notify the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) before making a ransom payment – the purpose of this was to enable ACSC to use the information it receives to better identify threats, to share information with law enforcement, and to track the effectiveness of cybersecurity policies.

There has been a significant push from the Coalition to introduce tougher penalties for ransomware gangs to deter future cyberattacks. The new Labor government has not indicated a desire to adopt the Coalition Bill despite the Minister for Cyber Security highlighting an “urgent need to address the conditions that have allowed the two largest cyber attacks in our history to occur within the space of two months”. Interestingly, Labor was supportive of the intentions behind the Coalition Bill when it was in Opposition.

With ransomware assessed by the ACSC as the “most destructive cybercrime threat” facing the country, we expect the Albanese Government to swiftly address this gap in Australia legislation – perhaps as part of reforms arising out of its Privacy Act Review. There is ongoing debate around how government can look to disrupt the ransomware business model, including through making payment of ransom illegal. However there is substantial opposition to this as a proposed approach, as it is seen as further punishing the victim of criminal behaviour and would likely disproportionately impact small and medium sized business. It will be interesting to see how this debate evolves and whether this is something the government entertains as part of the reform process.

6. Privacy Legislation Amendment (Enforcement and Other Measures) Act 2022 (Enforcement Act)

The Enforcement Act, which was passed by both houses of parliament on 28 November 2022 and came into effect on 13 December 2022, increased maximum penalties that can be applied under the Privacy Act 1988 for serious or repeated privacy breaches from the current $2.22 million penalty to whichever is the greater of:

- $50 million;

- three times the value of any benefit obtained through the misuse of information; or

- 30 percent of a company's adjusted turnover in the relevant period.

The Enforcement Act also:

- provides the OAIC with greater powers to resolve privacy breaches;

- strengthens the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme to ensure the OAIC has comprehensive knowledge and understanding of information compromised in a breach to assess the risk of harm to individuals; and

- equips the OAIC and ACMA with greater information sharing powers.

If the extraordinary changes to the Privacy Act laid out by the Enforcement Act (and enacted with such speed) is any indication of what’s to come from the Attorney-General’s Department, then the Australian privacy landscape may be in for a remarkable makeover. However, without a significant increase to OAIC funding, its ability to pursue such pecuniary penalties may be limited. It remains to be seen whether the financial threat will be viewed as a genuine deterrent by organisations.

In any event, it is clear that the recent data breaches have awoken the metaphorical bear and provoked the Government to take a harder stance than previously discussed during the Privacy Act reform process. However, industry bodies have warned against disproportionately severe penalties. There have been calls to introduce “safe harbour” provisions so that businesses that report in a timely way and act “in good faith” and “with due diligence” are exempt from penalties.

7. SOCI Act reforms

The original 2018 SOCI Act was focused on mitigating national security risks arising from foreign involvement, control or influence over Australia’s critical infrastructure. Over time, these risks have evolved and become more complex, with increased cyber connectivity and greater participation in, and reliance on, global supply chains (including with many services being outsourced or offshored).

In response to this, the Australian Government introduced various amendments to the SOCI Act in effort to enhance the existing framework. These reforms introduced a raft of new obligations, including obligations to:

- comply with new powers provided to Government to control organisations’ responses to cyber security incidents (including ‘step-in’ powers allowing the Australian Signals Directorate to take control of an entity's IT systems);

- create and comply with an ‘all-hazards’ risk management plan;

- notify the government departments about cyber security incidents under a new incident notification regime;

- provide the Australian Signals Directorate with ongoing access to systems information (e.g. server logs);

- create and comply with a cyber incident response plan; and

- undertake cybersecurity exercises and vulnerability assessments.

Importantly, the reforms also extended the scope of the SOCI Act to now apply to 11 critical infrastructure sectors (from the original 4 critical infrastructure sectors (water, electricity, gas and ports)) and 22 critical infrastructure asset classes. Certain critical infrastructure assets can also be nominated by the Minister to be “Systems of National Significance”, which subjects the responsible entity of that asset to enhanced cyber security obligations.

In light of scope expansion, a greater number of organisations are now subject to the SOCI Act obligations than was previously the case, either directly or as part of a supply chain that has been impacted by these reforms.

It will be intriguing to see the first explicit public exercise of ‘step-in’ powers under the SOCI Act and the effect of a government agency’s input into a corporation’s operations. It is possible that ‘too many cooks in the kitchen’ could actually compromise an organisation’s ability to effectively and efficiently respond to a critical incident.

Where to from here?

Against the backdrop of an increasingly complex and diversifying cybercrime ecosystem, it is critical that Australia’s regulatory framework surrounding privacy and cyber security operates efficiently and effectively, is fit-for-purpose and remains streamlined to avoid “compliance for compliance sake”. Duplication and complexity need to be minimised to avoid unnecessary red tape, which only results in diverting funds away from actual security-related activities that will uplift the ability for organisations to prevent these intrusions into their systems. Recent attacks on regulated entities serves as a reminder to organisations that due consideration must be had to all parts of Australia’s patchwork of privacy and cyber security laws – particularly given commentary from APRA that executive pay should be impacted when incidents of this nature occur.

Overall, the reforms, both proposed and enacted, reflect the Australian Government’s increasing efforts to enhance protections for personal information and risk resilience of Australian businesses as the economy looks to respond to new challenges in the digital era. With Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil recently announcing a program to develop a new cyber security strategy in Australia, it will be interesting to see if any accompanying legislative changes will emerge with, or as a result of, the new strategy. However, meaningful engagement from businesses who are in the process of dealing with cyber threats and adequate investment in regulators who are tasked with the mammoth job of working with industry to implement and enforce these regimes, will be essential for these reforms to be able to meet the government’s objectives.

1Financial services and markets; Communications; Data storage and processing; Defence; Food and grocery; Higher education and research; Health care and medical; Transport; Energy; Space technology; Aviation; Maritime transport; and Water and sewerage.

2Critical telecommunications asset; critical broadcasting asset; critical domain name system; critical data storage or processing asset; critical banking asset; critical superannuation asset; critical insurance asset; critical financial market infrastructure asset; critical water asset; critical electricity asset; critical gas asset; critical energy market operator asset; critical liquid fuel asset; critical hospital; critical education asset; critical food and grocery asset; critical port; critical freight infrastructure asset; critical freight services asset; critical public transport asset; critical aviation asset; a critical defence industry asset; an asset declared under section 5te of the SOCI Act to be a critical infrastructure asset; an asset prescribed by the rules.

No search results

The information contained in this article is general in nature, and is not intended to be a substitute for legal advice. Readers should obtain independent legal advice as to their specific circumstances.

PwC Australia

General enquiries, PwC Australia