Australia’s sovereign needs, capacity and capability

While not often a topic of national discussion prior to COVID-19, equitable access to essential medical products and technologies is a fundamental building block of a well-functioning health system. These products typically form the second largest component of health spending in most countries (after salaries)3, and at the most basic level require a nation to be able to supply:

Vaccines (e.g. flu vaccine) required for prevention

Diagnostics (e.g. blood glucose tests) required for testing;

Therapeutics (e.g. cold & flu medicines) required for prevention & treatment; and

Devices (e.g. surgical implants), consumables (e.g. personal protective equipment), platforms and technologies required to enable all of the above.

Whether these products are developed and manufactured domestically or sourced from overseas is primarily shaped by a number of factors: Namely the policy decisions, regulatory environment, investments and incentives provided by the public sector, and the resulting strategic choices made by global companies in the private sector, who evaluate each factor against competing, alternative jurisdictions.

In 2017, a national capability audit on medical countermeasures (MCM), conducted by the Department of Defence in consultation with 130 representatives from the Australian biotech community4, painted a concerning picture on Australia’s ability to meet its domestic needs. While noting Australia’s strengths in early stage discovery, research and clinical trials, the study also noted its lack of critical mass in end-to-end product development, scarce manufacturing facilities of limited diversity, critical shortages in talent and limited availability of non-clinical services. In line with these findings, manufacturers continue to reduce their presence in Australia, with the closure of local plants by multiple global pharmaceutical companies over the past decade.

Figure 1: Medical countermeasures (MCM) Australian capacity and know-how rating5

| Capacity | Know-how |

||

Therapeutics and Vaccines

|

R&D - non-clinical in-vitro |

B

|

B |

R&D - non-clinical in-vivo |

D | B | |

Clinical trials |

B | B | |

Manufacturing |

D | B | |

Regulatory science |

D | A | |

Project leadership and management |

D | A | |

Diagnostics and Devices

|

Requirements |

C | A |

R&D |

D | B | |

Assay development & manufacture |

C | B | |

Instrument development & manufacture |

D | B | |

Integration, validation & quality |

C | B | |

Animal and clinical studies |

D | B | |

Regulatory science |

D | C | |

Project leadership and management |

C | A | |

Key:

Capacity: A = Oversupply; B = Organised and scaled; C = Organised: D = Individuals

Know-How: A = Expert; B = Practitioner; C = Beginner; D = Nascent

Australia’s recent COVID-19 vaccine efforts illustrate some of these strengths and weaknesses. The University of Queensland’s (UQ) ‘molecular clamp’6 vaccine involves a collaboration between some of Australia’s leading industry participants in research, development and vaccine manufacturing, funded by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and advised by epidemiology experts.

While promising in its early stages, this vaccine represents just 1 of 132 candidate vaccines in preclinical evaluation at the time of writing, which sit behind 17 candidates already in clinical evaluation7 (the UQ candidate entered human clinical trials in July 2020). While other candidates are also being researched and trialled by various Australian institutions, the piecemeal involvement with other potential vaccines in part reflects Australia’s limited available capacity to evaluate and prioritise multiple candidates concurrently.

Under a best case scenario for Australia, where the UQ molecular clamp vaccine successfully progresses through clinical trials to commercial launch, the majority of doses will be made by a large-scale contract manufacturing organisation (CMO) partner8 who will almost certainly be located offshore. Should another vaccine candidate prevail, Australia’s access will be at best determined by the WHO equitable access guidelines, or alternatively by bulk purchasing agreements and the strength of its diplomatic relations, for which it is typically not at the front of the queue. And in the worst case scenario in which a vaccine is not discovered, the world will rely solely on therapeutic drugs - for which Australia’s manufacturing capability is notably scarce.

A long and complex supply chain

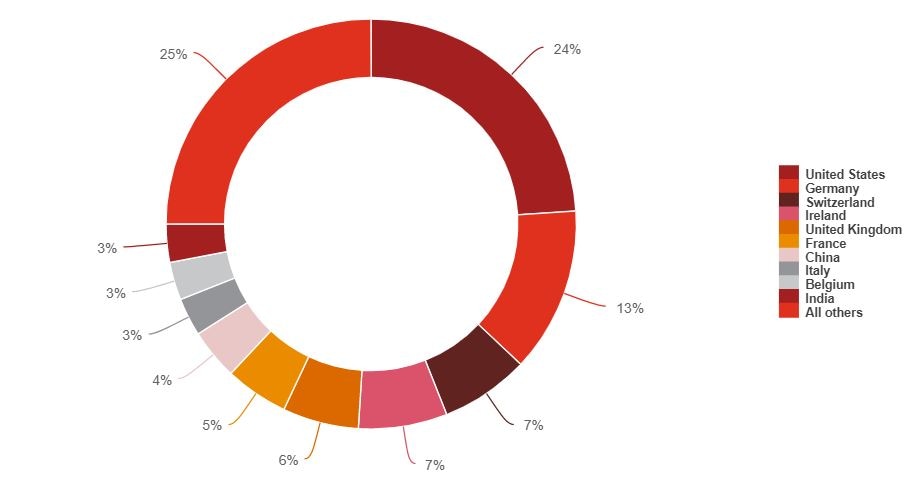

Due to limited domestic capacity, Australia sits at the end of a long and complex supply chain for the majority of its medical supplies, importing $16.6b of supplies9 and adding just $4.9b of value domestically10. According to DFAT statistics, medical supplies were imported into Australia from over 100 countries in 2018-2019, with the top 10 nations representing 75% of total imports, and the US and Europe alone representing ~68%.11 However, such statistics under-represent the complexity and fragility of the global supply chain.

Figure 2: Medical supplies - imports by trade partner12

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Composition of Trade Australia 2018‐19

While finished drug products continue to be manufactured by pharmaceutical companies in varying locations around the world, the US Department of Trade estimates that ~75-80% of underlying active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) (i.e. the part of the drug product which produces an effect) are sourced from India or China13. India alone exported around US$19b of drugs in 2019, and accounted for about one-fifth of the world’s exports of generics by volume14; it’s ‘Serum Institute’ claims to be the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer by number of doses produced and sold (more than 1.5b)15.

In turn, India sources an estimated 80% of key ingredients for medicines from China according to PwC’s Health Research Institute, including bulk API and precursor chemicals. As a result, a drug product purchased in Australia is likely to be imported from the US or Europe, containing an API produced in India, made from chemicals synthesised in China. Similar dependencies exist in the supply chains of complex medical equipment, in which high level assemblies, sub-assemblies and their underlying components have continued to transition to lower cost countries including China (particularly the emerging manufacturing zones in western China), Malaysia and Mexico, before being sold by med-tech developers based in the US and Europe who then on-sell to markets such as Australia.

The potential risks of a global supply chain failure are numerous and far reaching, as illustrated in the case of paracetamol (see case study below).